UE Toolbox Update - Parametric Assets, Open Source, and Hiatus

/The Gradientspace UEToolbox plugin is now both Free as in beer (on FAB), and Free is as in freedom (open-source, on Github). I’ve given up any hope of sales of this plugin funding it’s development, and Epic declined to fund it via their MegaGrants program, so for the time being I will be putting this plugin on the shelf. Further down in this post I’ve written up a sort of post-mortem, on what I tried to do, what went wrong, and (possibly) why.

But first, since I’m moving on, I figured I might as well release the next major feature I was working on, even if it is not quote polished - Parametric Static Mesh Assets. And so I wrote about the fun stuff first, and the sad stuff second.

And if you are looking for UE development consulting, maybe to help with shipping a plugin of your own, please get in touch!

The Good - Parametric Static Mesh Assets

From my first days working on geometry in UE, I was thinking about how to do parametric/procedural geometry. The problem with doing this in UE is that you are fighting the Engine at every turn. Complex 3D games are built primarily with static geometry, and so the “Static” in Static Mesh is baked into UE in hundreds of tiny ways that you’d never imagine until you are down in the guts of the code.

Eventually I got to Geometry Script, which did allow procedural geometry - but only on a special mesh type (DynamicMesh) that was Not a Static Mesh. That means it doesn’t have Nanite or Lumen or many other performance and memory optimizations that only a StaticMesh has. And that effectively means it cannot be used in Serious UE Games.

So, for the past year or so, I have been spending some time on this feature set that (IMO) plugs a huge gap in the UE procedural-geometry ecosystem. Something that absolutely should be built into UE, and I really wish I had thought of it years ago. But for now, what I can leave you with is this sorta-janky prototype.

The problem I was trying to solve was one that every tech artist who tries to use Geometry Script to create procedural mesh Actors will run into - the whole thing only really works with DynamicMeshActors, which are not StaticMeshes. DynamicMeshComponent is really designed for live-editing, so it doesn’t support expensive Nanite or Lumen build steps, is not memory-efficient, can’t be instance-rendered, and other things. And for those reasons, no serious game uses DMCs. So everyone using GeoScript in their design process has to have some kind of janky “bake to StaticMesh” process.

On Epic’s Lyra project we cobbled together a system where we tracked relationships between the procedural DynamicMeshActor (DMA) and a baked StaticMesh, and the placed StaticMeshActors, and could ‘swap’ the DMA in place of the StaticMesh to do live editing. But the DMA’s had to stay existing in the level - our “swapping” operations just hid them far below the ground plane. Total hack. Also the tracking system lived in the level and didn’t support multi-user editing and caused tons of problems. Inside Epic I saw another way become popular, using an Editor-only ChildActorComponent with the procedural generator that bakes into the StasticMesh of the parent Actor. But this only works with a single instance, and has it’s own problems.

What you really want is a StaticMesh asset that has the GeometryScript attached to it, and any instance of the StaticMesh in the level can be “made editable” temporarily. Like the Lyra system but without the janky swapping thing. So that’s what I did.

The video above-right shows what this system can do - in the foreground is a StaticMeshActor with a parametric StaticMesh Asset assigned, and in the background is an InstancedStaticMeshComponent with 10k instances of that same StaticMesh Asset. Using my Edit Parametrics Tool, I can tweak settings of the parametric generator for this Asset (generates a sphere, applies PN Tessellation, and then Displacement). When I click the Rebuild button, a DynamicMesh is generated using the new modifier stack, and then use to update the StaticMesh, which means that all 10k instances reflect the new StaticMesh too.

UGSDynamicMeshProcessor

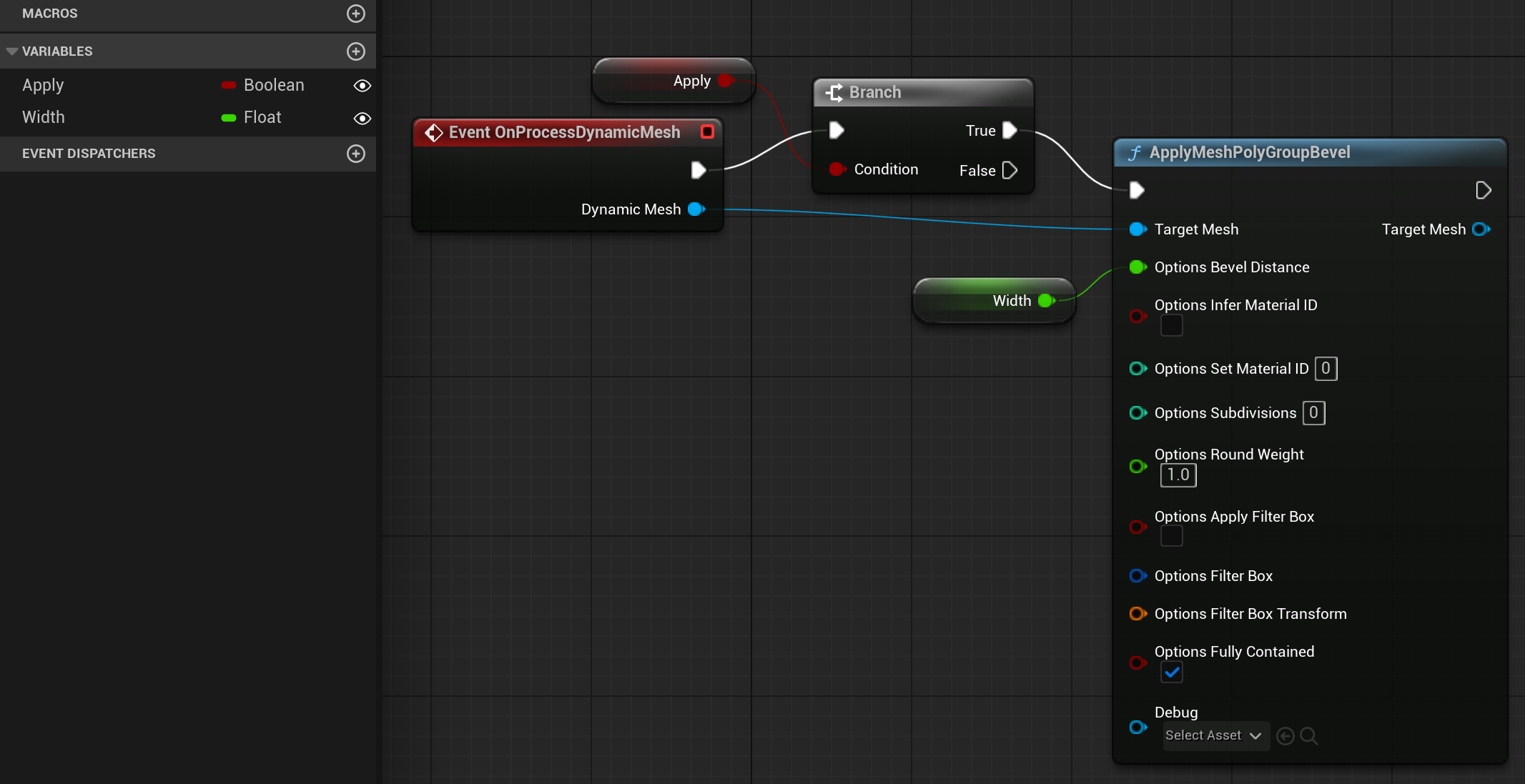

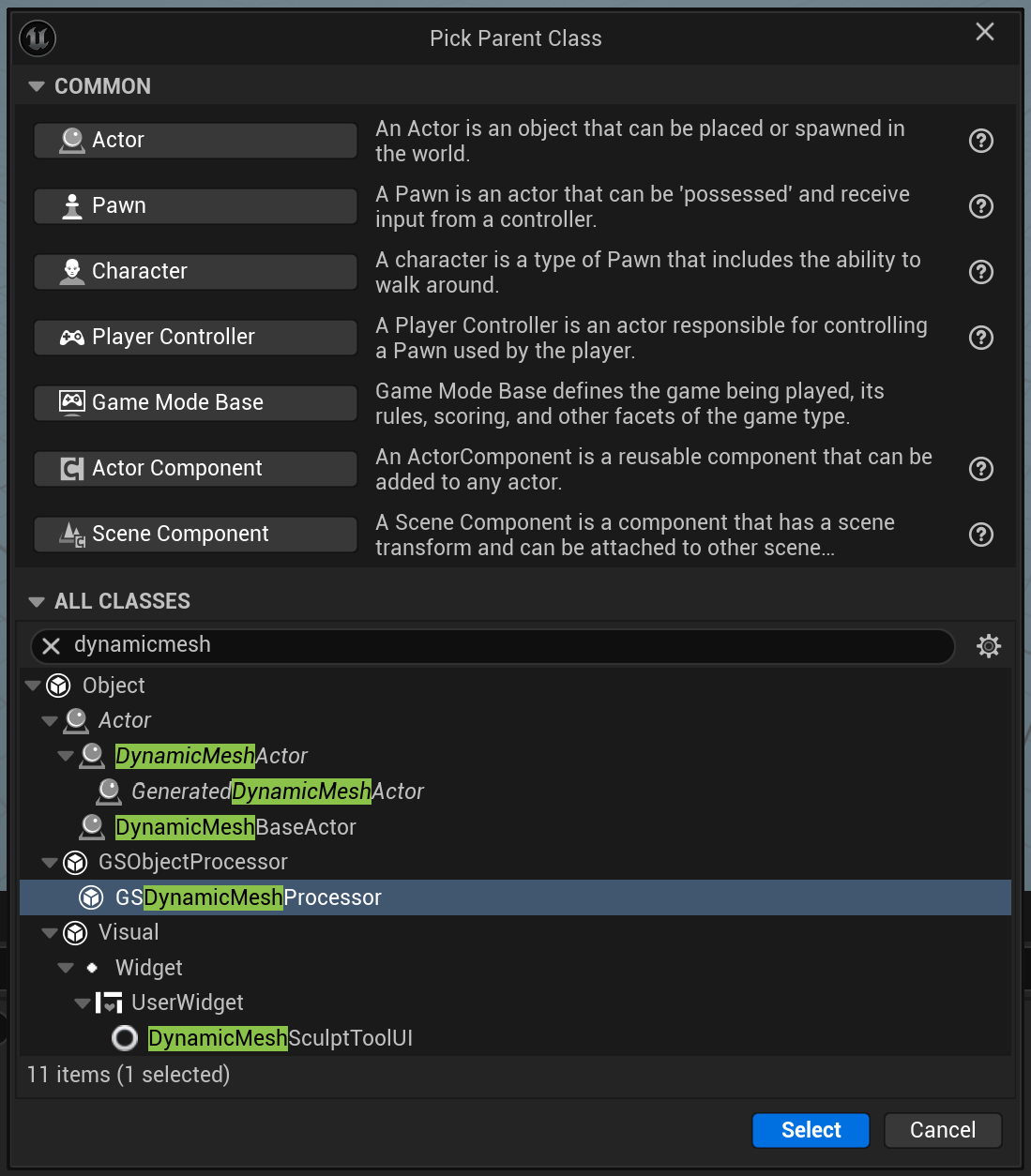

The first thing I did was create a Blueprintable base UObject class UGSDynamicMeshProcessor for procedural DynamicMesh processing that was not connected specifically to Actors, Components, or Editor Utilities. The class just has one Native event, OnProcessDynamicMesh(), similar to GeneratedDynamicMeshActor’s OnRebuildGeneratedMesh. However this one can be implemented in C++ or in a Blueprint subclass of this base class, so this is not a BP-specific system and the procedural stuff could alternately be done in C++ (avoiding a mistake I made with the DMA design…). Simple examples that Generate a Box and Apply a Bevel could be set up as shown in the images to the right

By itself these objects won’t do anything - but they can be used by things that want to generically process or generate a mesh. So, for example, a GeneratedDynamicMeshActor (GDMA) could call a DynamicMeshProcessor to do some or all of it’s mesh modifications. The intention here was to decouple the mesh generators/algorithms from Actor BP graphs, which allows for management and re-use of the mesh generators in other situations (as we will see below).

I also made a UGSStaticMeshProcessor, which has a similar function but takes a a UStaticMesh instead of a UDynamicMesh. Both the Static and Dynamic versions share a base class, UGSObjectProcessor, which will be useful later.

UAssetUserData

Now my goal was to create a “parametric” StaticMesh Asset, ie an Asset that has a mesh generator attached to it - in the form of a UGSObjectProcessor - that can be run to generate the Asset’s mesh based on parameters. So, eg, you could have a parametric box - like you can easily create with a GDMA / DynamicMeshComponent - but the parametric-ness is on the StaticMesh Asset, not on Actors or Components in a level. So (like the video above) if you parametrically edit that Asset, any placed instances in any levels will reflect the new mesh, and so on.

To do this attachment I used UAssetUserData, which is a way to attach arbitrary serialized UObjects to various asset types, including UStaticMesh. I made a pretty simple class UGSStaticMeshAssetProcessor which has a Native event OnProcessStaticMeshAsset() that again can be implemented in C++ or BP. And then I made a subclass UGSStaticMeshAssetGeneratorStack, which is a bit more structured - in very rough pseudocode it basically works like this:

class UGSStaticMeshAssetGeneratorStack : public UGSStaticMeshAssetProcessor

{

UGSDynamicMeshProcessor MeshGenerator;

TArray<UGSDynamicMeshProcessor> ModifierStack;

void OnProcessStaticMeshAsset_Implementation(UStaticMesh* StaticMesh)

{

DynamicMesh GeneratedMesh = NewDynamicMesh();

MeshGenerator.OnProcessStaticMeshAsset(GeneratedMesh);

foreach (MeshProcessor in ModifierStack)

MeshProcessor.OnProcessStaticMeshAsset(GeneratedMesh);

StaticMesh->SetMesh(Mesh);

}

}So once the initial MeshGenerator is set up, and optionally the additional ModifierStack, then the OnProcessStaticMeshAsset() function can be called (either by UE C++ systems or by a BP) to rebuild the static mesh based on the Generator.

It’s actually even more configurable than this, the generate-and-apply-modifiers and the copy-to-static-mesh are both also NativeEvents that can be overridden in C++ or BP to modify that behavior too. Perhaps now it’s clear what role the UGSDynamicMeshProcessor plays - the parameterized static mesh can be broken up into (eg) a base shape generator and separate re-usable Modifier implementations that do things like (maybe) subdivide-and-displace, configure materials, add greebles or bevels, configure settings for specific type of assets, and so on.

A critical thing to note here is that this does not involve (eg) a subclass of UStaticMesh. The StaticMesh Asset is not dependent on the processor AssetUserData, and at any point that AssetUserData can be stripped off and the StaticMesh will just stay in it’s current state - it doesn’t even need to be rebuilt. So it could (eg) be done during cooking. And if the AssetUserData is marked Editor-only, it will automatically be stripped out during the game build (actually it becomes a nullptr, but the system knows how to handle this).

This system achieved my goal of “making a StaticMesh be inherently parametric/procedural without a major overhaul of how StaticMesh works”. It’s is incredibly flexible and my real regret is that I don’t have any great examples of what you can do with it!

User Interface

One question remains - how do you actually edit and update a Parametric Static Mesh? I had big plans here - I wanted to build a system where if you selected a StaticMeshActor w/ a parametric Asset, you would get options in a details panel and in-viewport popup controls/widgets like you can get with a GeneratedDynamicMeshActor. And I wanted to have a back-end Subsystem that was monitoring all the various Processor BPs/implementations/parameters, and if any changed, now-possibly-dirty Assets would be marked for rebuild. But to avoid the “oh shit now every Asset in my entire project is rebuilding”, I was going to have that Subsystem have a UI where you could (eg) defer rebuilds and kick them off when you went for a coffee.

But it was not to be. So instead what I have is an Interactive Tool you can run on StaticMeshActors with parametric Assets, which exposes the public UProperties and BP-defined public variables of the Processors, and allows you to rebuild the Asset while the Tool is active.

One thing that is lost here is that extremely handy feature of Actor BPs where you can mark an FVector variable as having a 3D widget. So I figured out a way to do that, too. How it works is, the base UGSObjectProcessor class has an implementable function OnRegisterPropertyWidgets which you can implement in BP to register widgets and callbacks. That function is passed a IGSObjectUIBuilder object, which is similar to the way some things are done in ScriptableTools - it has some API functions like AddVector3Gizmo and AddTransformGizmo that you call from the OnRegisterPropertyWidgets implementation to hook up a 3D translate or full 3D transform gizmo to a UProperty of the compatible type (eg FVector or FTransform). The image on the right shows an example of a DynamicMeshProcessor that does a plane cut, where a Transform Gizmo is configured for the FTransform variable (called “Plane”) used to define the cutting plane.

The ParametricAssetTool calls this function on each Processor it finds (via some helpers on UGSStaticMeshAssetProcessor) to collect up the Widgets that need to be created, and do the hooking-up-to-properties. So when you run the Tool on a Parametric Static Mesh Asset, you magically get the little handles/etc. I had intended to build out a larger library of predefined gizmo types, but…

So the result is that in Edit Parametrics Tool, you get a little UI to build up the Processor Stack on a StaticMesh Asset, and the public Variables of the various processors are exposed in the Tool settings area. As you modify the settings, the stack is executed and the StaticMesh is rebuilt. This can either be done live (with the Autobuild on Changes checkbox), or you can disable that and use the explicit Rebuild button.

Limitations

This system is still a prototype for one main reason - it is quite tricky to handle live-editing of the DynamicMeshProcessor BPs while the Tool is active. This is obviously the primary thing you want to be able to do, because you want to see the mesh update as the BP is modified and recompiled. However at the C++ level this is a very hairy situation, because as soon as the BP is recompiled, a lot of C++ pointers/etc are now pointing to invalid things. And so we need to tear down everything. And unfortunately BP only has very basic event signaling around BP recompiles - basically there are only very general events GEditor->OnBlueprintPreCompile() and GEditor->OnBlueprintCompiled() that we can hook into. And since a DynamicMeshProcessor could be (eg) nested, we have to do this any time any BP is touched (as I couldn’t figure out how to detect BP dependencies).

We also have to handle live changes made to the structure of the UGSStaticMeshAssetGeneratorStack, eg adding or removing modifiers, and their properties which could be quite complex. Because some of those things are “mine” I could add robust change-signaling. However Undo/Redo still is hard to handle because UE does not provide object-specific callbacks for it. So, ultimately, I spent a while tracking down cases where things went wrong, and ironed out most issues. However it’s possible if you are doing a lot of modifications to the modifier stack while the Tool is live, you might hit crashes. Sorry!

Another thing that just rubs me the wrong way about this whole system is that while the static mesh is async-rebuilding, it will flicker. This is not something I can do anything about, it’s inherent in how StaticMesh works. But the result is that it looks kinda janky, as shown in the video below. This is why I made DynamicMeshComponent in the first place - to avoid having the live-update refresh rate being capped by the not-insignificant cost of the StaticMesh rebuild (and affected by however the SM system decides to handle updates - eg by flickering…). I had some ideas about hiding the StaticMesh and swapping in a DynamicMesh while editing, but as you see later in the clip, this won’t work for all the other instances of the StaticMesh in the level.

The Bad - UE Toolbox Post-Mortem

When I left Epic, I had a big plan and a little plan. The big plan, well that’s still in progress. But the little plan was to make an Unreal Engine plugin with a bunch of great Editor Tools for game developers and artists. After creating and working on UE5’s Modeling Mode and GeometryScript for ~5 years, I had a laundry list of things I wanted to build that (a) I was pretty sure users wanted and (b) that Epic wasn’t focused on. Things that, if I had stayed at Epic and added them to Modeling Mode or the Editor, I was certain would have been a big hit with users. So my hope was that I could develop and sell this plugin, and those sales would fund the first baby steps of my big plan.

I spent a good chunk of 2024 working on the plugin. I started with some HotSpot texturing tools, but never actually included this in the shipping build. I wanted to try to advance the state-of-the-art in HotSpot texturing, and I needed to do quite a bit of geometry work to get there. So instead I pivoted to focusing on a parametric grid-based modeling system that eventually became ModelGrids.

Parametric Voxel-y Grids for UE

I focused on ModelGrids for a few reasons. One, it’s a core part of the big plan and so I wanted to make some progress on proving out my concepts. Two, voxel-based modeling is just inherently something that nearly everyone understands, due to it’s popularity in (eg) Minecraft, Magica Voxel, and other games and gamedev tools. And three, UE’s CubeGrid Tool was a huge hit with Modeling Mode users, but had (IMO) some major limitations. In particular it doesn’t support any kind of parametric or non-destructive editing - it’s not actually voxel-based, it’s a grid-based mesh editing interface. And that constraint rules out so many use cases, in particular any kind of in-game usage or the ability to use it as a starting point for (eg) GeometryScript mesh generators. So this seemed to me to be a clear place where I could do something good.

I started on ModelGrids almost immediately after leaving Epic, posting the first video of a working prototype on Jan 31st, 2024, and released the first version on November 5, 2024, after a few months of development teasers that got decent response on pre-jackpot Twitter (as far as this kind of thing goes, for me). The initial release included ModelGrid Assets & Actors, ModelGrid editing tools, and MagicVoxel import, as well as a few related tools for Polygon Mesh import and export - in particular, Polygon-to-Polygroup import, a much requested feature that for technical reasons was very hard to implement in the standard UE FBX importer. And a pretty cool fast-mesh-positioning tool. Even in the first release, this was a substantial plugin, doing much “more” than most UE plugins you will find, particularly in terms of Editor Tools. It solved real problems that I knew people had. It seemed like someone would be interested!

Initial Release

I did not want to go through Epic’s FAB store for reasons I will explain, so I opted for releasing binary builds of the plugin via zip files on my website, as a free download. My intention was to eventually figure out how to charge for commercial use, or set up a Patreon to fund development. So I spent a while making a nice plugin website - https://www.gradientspace.com/uetoolbox - and posted it everywhere I could think of.

I knew zipped-binary-builds were not an ideal distribution mechanism - the user has to manually download the zip file and extract it in the right place in their UE project or Engine source folders. Being binary-only meant that anyone using a source build couldn’t (easily) use it, and I was only supporting Windows. Precompiled binary plugins are also UE-version-dependent, which means when a user upgrades engine versions via the launcher, they need to go and explicitly upgrade my plugin too, or their project will be broken. I wrote an auto-update script to try to make this less painful, and I made a detailed tutorial video about how to deal with installation. Still, I knew it would be an advanced-users-only setup, and my plan was to eventually build a proper installer “for the masses”. But I also knew that some substantial widely-used UE plugins are distributed this way, so I figured it would be acceptable starting point.

Well, it wasn’t. Despite a lot of likes, I could see that only a handful of users downloaded the plugin. I was not expecting a huge response, given all the complications, but I was hoping for some enthusiastic early adopters who would provide feedback and help to steer me towards useful features, and it just did not happen. I had one single user reach out about ModelGrids, and that was it. Clearly something wasn’t working. My hypothesis was that the focus on ModelGrids wasn’t landing, and I needed something with a clearer and broader value proposition. So I switched to something I was certain that people wanted in the Editor - Texture Painting.

Pivot to Texture Painting

If you are familiar with all the nooks and crannies of UE, you might know that the UE Editor has an extremely janky 3D Texture Painting tool hidden in the old Paint Mode. Epic had just released their ‘Texture Graph’ plugin for node-based texture creation (which has not seen much further development), getting people excited about making textures in the Editor. Texture Painting had always been a frequent request for Modeling Mode, and there were a few pretty basic options out there, but I knew I could do it better. And so in December 2024 I added an initial Texture Paint tool to the plugin, and cranked out updates every week until January.

Now, you might think 2 months is not that much time to build something like this from scratch, and so it can’t possibly be more than a quick-and-dirty prototype. But inside UE, where you have so much infrastructure available, it’s possible to build advanced capabilities very quickly. I could leverage all the Geometry tech, and the existing Texture and Material systems, that normally would be a huge amount of work to get going in a standalone creative tool. So this Texture Paint toolset…it is solid. I know that if the UEToolbox texture tools were shipped as part of Modeling Mode, they would have been a big hit. But as a third-party plugin…still crickets. Good response to social media posts, and people were downloading the updates - but still in very small numbers (10’s of people, not 100’s). And nobody was pointing out bugs or asking for features - literally nobody at all.

Pivot to FAB

By March 2025 it was clear that there were not enough users out there to start charging money, or ask for Patreon donations. So I decided to put aside my reservations about FAB and post UEToolbox there. My issue with FAB is that to publish a UE plugin you have to include all UE-dependent source code. Epic needs your source to be able to compile your plugin into binary form, which is what most users download (ie exactly what I was shipping via zip file on my website). Epic also requires that you make that same source available to all buyers, because if the buyer is using their own Engine build, they need to compile your plugin against their custom Engine build. The latter is why I had avoided FAB - it’s effectively requiring your plugin to be open-sourced, which means any unscrupulous user can trivially share copies. And people do - there are entire websites (run out of countries with lax IP laws) that simply buy FAB plugins and re-sell them, calling it a “discount site”/etc. This (IMO) is one of the biggest reasons that UE has such a weak third-party ecosystem. But, it seemed like I was going to have to join it anyway.

However, it’s still possible to ship non-UE-dependent parts of your code as precompiled binaries via FAB. So I refactored my plugin to have some core libraries that were independent of UE, and could be precompiled into binary DLLs. I used Microsoft’s Azure Trusted Signing service to sign the DLLs. This doesn’t prevent copying, but it would at minimum allow me to prove that a copy was a copy. I had to give up on really being able to protect any of my UE-dependent code (ie most of the plugin) but at least I could have this tiny bit of control.

A small sidebar on “give up on on being able to protect my code” - the standard thing people want to say here is “IP laws and legal system protects you” / “you can sue” / etc. That’s completely implausible for a small indie developer, for many reasons. Large corporations like Epic have that kind of protection, but a small operator does not. The cost to pursue even a slam-dunk IP infringement lawsuit (likely across international borders) is easily in the tens of thousands of dollars. And unless the infringer is a large entity with deep pockets, it’s very unlikely I would ever recoup those costs. The most I could plausibly do is send cease-and-desist notices and hope that people buy a license.

But even worse, since my plugin was primarily Editor tools, it can be used during game development without ever appearing in (eg) a shipping game build. A copied/stolen plugin that is part of the game exe is at least easy to identify. And a plugin that creates in-game dependencies needs to be installed on every build and development machine for the Editor to be able to load the content. But Editor tools don’t have this constraint - my plugin can be used by a single user of a project, without creating any asset dependencies. I consider this a good thing, but it does mean that (eg) a few people in a studio could share a copy without the studio even knowing, or having to think about licensing it.

So, after jumping through all the hoops to get a source-plugin-with-binary-dependencies through the review gauntlet (not trivial), the FAB version went up in early March. I priced it at $25 USD for regular users, $50 for “professionals” (FAB decides standard vs pro based on revenue, > $100k means you are a pro). This was a very low price point for what the plugin does! Many UE plugins on FAB are hundreds of dollars. My hope was that this low price would result in more users, which was more important to me than money. I needed people using this plugin, and talking about it.

I tried again with the social media posts. And I started to see a few sales. Not many, but I was hopeful. In fact this was the first time I had ever actually sold software that I made directly, which was kind of exciting. April came and went and I had done…not bad for the first month. And then in May, it slid back down to just a handful of sales. The bump had come and gone, and I had sold about 30 copies, for about $700 USD total (about $1000 CAD at the time). Precisely zero buyers had submitted a rating on FAB.

Pivot To Free

At this point, I was very discouraged about this plugin. I knew I was still probably limiting my user base because I had these binary DLL dependencies, which meant the FAB version was Windows-only. But I was not ready to let that go. So in June I made the plugin completely free on FAB, for all users. Now, a frustrating aspect of FAB is that they don’t appear to report free usage at all. So I have no idea of whether or not this made a difference to downloads or usage. All I can say concretely is that as of August 1st, the plugin has a perfect 5.0 stars from 12 ratings. On FAB, this makes it one of the top plugins in the ‘Modeling’ category. Anecdotally, other plugin devs have said somewhere between 1 in 10 and 1 in 100 users submits a rating. So, that was promising…as long as it was completely free.

Unfortunately, completely free is not sustainable. Conservatively, I spent about a half a year working on this plugin. Based on the average Epic Games L5 Engineer salary at levels.fyi, that’s at least $250k of opportunity cost (and I was a Fellow, which at Epic is above L6…). I made about $700. So, it’s been quite a money-loser 💸💸💸💸. When I started the project, I had set a rough guideline that the plugin needed to bring in about 60k a year for me to keep working on it part-time, and if that didn’t seem plausible, I would have to re-evaluate. So it wasn’t looking good.

My last-ditch attempt to continue working on the plugin - which I really wanted to do, I had so many cool plans - was to try to get a MegaGrant. This is a program Epic has to fund external projects with proceeds from Fortnite. It does lean heavily towards UEFN and game projects, but they have funded many UE plugins in the past. At Epic I had been a Megagrants reviewer, mostly for Editor plugins, and so I knew the odds were low, but not zero.

(Final) Pivot to Open Source

Well, it was not to be. A few days ago I received the rejection email. And so, here we are - I’ve fully open-sourced Gradientspace UE Toolbox. The FAB version now includes the full source, ie no more precompiled DLLs. For the Github version, I decided to use the MPL2.0 license, which means you can do whatever you want with the code, but you also need to release your changes to my files as MPL2.0-open-sourced. This is known as “weak copyleft” - it does not virally infect your codebase, the license applies at the file level and is only concerned with the source code text, not binary linking/etc. If you are a gamedev or studio and find this concerning, you can still (and should) get the FAB version under the FAB standard license, which is ideal for how UE gamedev works. The MPL license only applies if you want to publicly redistribute the plugin source code, and just prevents unscrupulous people from zipping it up and re-selling it. And I’m open to other licensing arrangements if you have a good reason (if so, please get in touch!).

What went wrong?

Plugins are Not a Great Business

Steve Jobs famously tried to convince the DropBox founders to sell by telling them they were “A Feature, not a Product”. The promise of Plugins is that you can, effectively, sell Features without having to build a Product. But when you sit down to make a plugin, you have to accept that your userbase is fundamentally capped by the userbase of the larger Product. UE is very popular, but Modeling Mode “only” has something like 100k active users. What percentage of those users want procedural grid objects or texture painting? Optimistically perhaps 10% might be interested…and perhaps a further 10% of those people might ever hear about my plugin or bother to try it…so we are already down to small numbers! And there is no way to grow that pie - nobody is going to adopt Unreal Engine just to use my Tools.

So, my hopes for this plugin were probably misguided from the start. For the average UE user, their only real experience with this kind of toolset is that these tools come for free as part of the UE Editor. There is a very small ecosystem of plugins like mine, so most UE users are not expecting to find capabilities like this in a FAB plugin. It’s definitely possible that I just had grossly over-inflated expectations about what users might be interested in. Certainly ModelGrids won’t have a huge place in most projects. But Texture Painting is pretty universal! 🤷♂️.

It’s hard to even find a real point of comparison. The Scythe Editor plugin is perhaps an illustrative example - this is a similar “Editor Geometry Tools” plugin, providing a Valve-Hammer-like interface inside UE. There is a userbase of game developers that were absolutely gagging for this kind of stuff in Modeling Mode (and harassed me about it constantly…). UE luminaries like Joe Wintergreen are talking up this plugin all the time. It’s funded via Patreon and looks like it makes about $1400 USD a month right now. So it’s doing much better than UEToolbox, but still nowhere close to my threshold. (BTW Scythe Editor is awesome and you should absolutely get it!!)

Lack of Focus…

Frankly, the approach I took of “adding a bunch of things I think UE Editor is missing” was probably not ideal. Most UE plugins are pretty focused on “one thing”, ie a plugin for a specific problem or task. This, of course, limits how much they can ever expand and grow. But it also makes it much easier to explain the value proposition. Even my name - “UE Toolbox” - is probably too generic. I didn’t want to box myself in by getting too specific. My thinking was always “eventually it will be a comprehensive suite of tools”, because that’s basically how I went about building both Meshmixer and Modeling Mode (if you went back and looked at UE 4.24, Modeling Mode has about 10 tools that seem completely arbitrary…but there is a clear evolutionary line to the ~80 it has now!). But, it clearly didn’t work for selling a Plugin!

Certainly it did not help that “Creating Assets in UE” (ie meshes in Modeling Mode, textures in Texture Graph) is still a relatively new concept and not on the radar of most game artists. Artists who need to create textures are going to Substance/Blender/etc. I wasn’t really trying to compete with those behemoths - but being able to do some texture editing or creation directly in-Editor is hugely valuable! Things like painting masks or “functional” textures (ie to drive procedural Materials or parametric Shapes), quick touch-ups, etc, can save a ton of time. But it takes years to get people to see this and modify their practices. On Modeling Mode we saw that a big barrier can be studio policy - many studios require ‘source files’ (ie the maya/fbx/blend/pngs/…) for each game asset be checked into a content management system in specific ways. Assets created in-Editor don’t have source files and so require exceptions or policy changes that can be hard to achieve in a large organization.

The Gamepocalypse

It absolutely did not help that I set out to build Gamedev Tools right as Gamedev was imploding. Roughly 30% of the industry has been laid off in the past 3 years, with an enormous number of studio closures and game cancellations. Some days it seems like Gamedev Bluesky is mainly people looking for work or asking for help to make their rent. The survivors are heads-down trying to ship their current project before funding runs out or plans are scaled back.

I get the sense that interest in UE as a non-game platform has also been tempered. Many of the early adopters of Modeling Mode and GeoScript were from outside of gamedev, in adjacent industries like Virtual Production or “Enterprise”, or trying to use UE as a development platform for Apps or Services. However these userbases are small, and now Epic has been focusing more and more heavily on UEFN, which doesn’t really offer anything to non-game UE users (and doesn’t support UE plugins at all 😢). Those are the kind of users who I had hoped to connect more directly with, but they are hard to find.

Ultimately although UE looms large in the gamedev world, and I personally think it’s an amazing development platform, it’s a niche platform in the larger tech industry. Before I joined Epic (from outside the gaming universe) I didn’t know a single person who used UE. Many academic and industrial labs experiment with Unity, but UE has such a steep learning curve, and high technical requirements, that it is not widely used outside games and high-end VFX. I can’t count the number of times I encouraged someone to try out UE, only to have them discover they couldn’t run it on their laptop GPU, or they didn’t have a few hundred free GB of disk space. So, I was fighting some serious headwinds on this front.

Marketing

One thing that I definitely could have done better was marketing. In the past I have always been able to rely on my personal social media channels to get the word out about my projects. This worked wonders for Meshmixer and UE5 Modeling Mode. Epic’s UE Marketing team really ignored Modeling Mode - you will be hard-pressed to find the single short demo video that was produced (thanks Sam!!). The main place users went to find out what was new in Modeling Mode was my personal Twitter feed, and for tutorials and learning materials, my YouTube channel and this very website.

However, the disintegration of Twitter has meant that there is no similar focused place where you can reach a large number of users. BlueSky is great, it’s my new everyday social media, but it does not have the UE or graphics/technical userbase that peak Twitter had. And the lack of an algorithmic feed means that I have to re-post my own posts to make sure they are seen, which I personally find very hard to do. Mastodon came and went, and Instagram/Threads isn’t it either. Reddit seemed like it had potential, but it’s more of a one-shot type of thing, you make your big post and hope it doesn’t immediately get bumped down by something more popular (and the biggest channels require you to have a substantial Reddit history). Maybe I should have tried…TikTok?

I certainly should have hired an artist to make some higher-quality example content. My examples are all very basic because I don’t actually paint textures or do creative modeling myself. I did try several YouTube demo/tutorial videos, which have always worked well for me in the past. Between my Meshmixer and Epic YouTube channels, I’ve had over 1.5 million views of demo/tutorial videos I personally recorded and edited. But over the course of a year, my launch video has racked up a whopping 1.1k views, and as of today, the ~20-minute tutorial on the Texture Paint workflow has 457 views. I posted it everywhere I could think of…it just did not land.

No Feedback Loop

Ultimately I needed some early adopters who were excited about the project and who wanted to talk about it, and I couldn’t find them. Early adopters of Meshmixer, Modeling Mode and Geometry Script had an enormous impact on what features I pursued. Without some positive reinforcement, it’s very hard to stay focused and motivated to push a project forward. And I just couldn’t find anyone who was into it. Lots of “this looks great” but never any follow-up. So far not a single person has ever posted a bug report or feature request for the plugin on my Discord, and I’ve never seen a single image of a ModelGrid or painted-in-UE texture anywhere “in the wild”.

This is what really led me to decide to shelve the project. I can work on a thing that doesn’t make any money. But it turns out I can’t work on a thing in a vacuum.

Something curious did happen, though. I twice had someone reach out and say “I normally would never bother a developer with comments but…”. Almost like they were pre-apologizing for any offense I might take? It made me really wonder about something that I felt like was often happening with users of Modeling Mode, which was that people so want to avoid being a source of “toxic feedback” that they self-censor to the point of not giving any real feedback at all. We often found ourselves literally begging users - even internal users - to tell us what they thought of features. And eventually they might say “well I use it all the time but it would be great if…”.

The one thing that keeps a project going is people talking about it - good or bad. I often describe myself as “complaints-operated” - of course I’d like you to sing my praises 😁, but actually some harsh truth is often more useful, and barring either, just hearing that someone out there used my thing is so, so motivating. So if you are a user of things - particularly Tools - tell the people who make them! Small indie developers are not faceless megacorps logging your every action! They are a handful of people and they need your feedback - good or bad - as much as they might need your financial dollar support. People who develop the Tools in the early part of your pipeline will hardly ever get credit for the cool thing that comes out at the end, and often won’t even be able to tell if you are using their Tool at all. Tell them!!!

Parting Thoughts

Looking back at my post from November 2024 launching this plugin, I can’t say I’m surprised with how this turned out. I noted in the post that this plugin seemed like a random collection of features, and it still feels that way. I also was aware that a UE Plugin was inherently a problematic way to try to ship new creative tools like ModelGrids…but I did it anyway. When I was at Epic, working on Editor Geometry Tool plugins that could only be updated a few times a year due to shipping as part of the larger UE machine, I was certain I could do it faster and better. And I proved that I could, at least to myself. But it turns out, it doesn’t seem to really matter to users :(

I can’t really see myself continuing to work on Tools for Unreal Editor, which is a major bummer for me as I really, really like working with Unreal Engine. In a sort of irrational way. A lot of C++ coders have valid complaints about how UE does things, but it doesn’t bother me at all. Maybe it’s because I do so much C# in my other projects? For building Editor Tools, Garbage Collection is fantastic, the UObject system is super powerful, and infrastructure like Details Panels is a huge win. So I find creating tools within UE Editor to be both very efficient and very satisfying. That might be surprising to other developers who have tried it. But once you know the codebase like I do, working around it’s limitations is not hard, and there is so much functionality to draw from. The only thing I really struggle with is getting efficient rendering…which is weird since it’s the thing UE is known best for.

So it’s really unfortunate for me personally that this platform where I can be super efficient and crank out powerful Tools, is just not a good place to actually get those Tools into the hands of users. UE is primarily a platform for game development, and game developers have never been my main user constituency. I found little islands of overlap in different areas of gamedev, particularly around some aspects of tech art, but it’s not enough. Most of my potential users simply do not use Unreal Engine, and nobody is installing Unreal Editor just to play around with my ModelGrids editor (which they probably wouldn’t even be able to find in the UI!).

When I left Autodesk, I had to leave Meshmixer behind. I didn’t have the code, so it was out of the picture. It still took at least a year before I stopped reflexively searching for new tweets from users and replying with tips and troubleshooting. Getting UE out of my head has been much harder, because I can literally close this blog post and go and implement one of a hundred ideas I have to improve Unreal Editor, and possibly even ship it by the end of the day. This is extremely addicting for a Tool Maker. But it doesn’t work, and I need to focus on other projects.

So, look for a new nodegraph progamming tool for C# and Python, coming soon!

demo of my in-development nodegraph programming tool. A “code node” with embedded C# is used to dynamically create and return a C# Func<> function/lambda, which is passed to a generic mesh-deformation node, that evaluates the function for each vertex